Golang gron

ag9920 人气:0

cron 简介

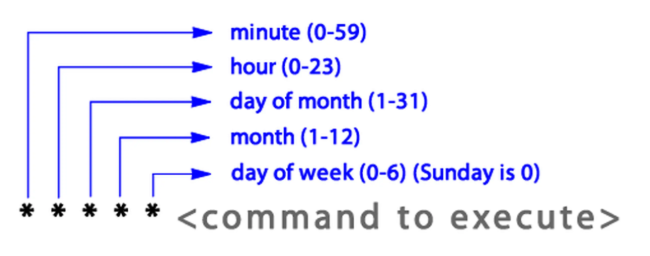

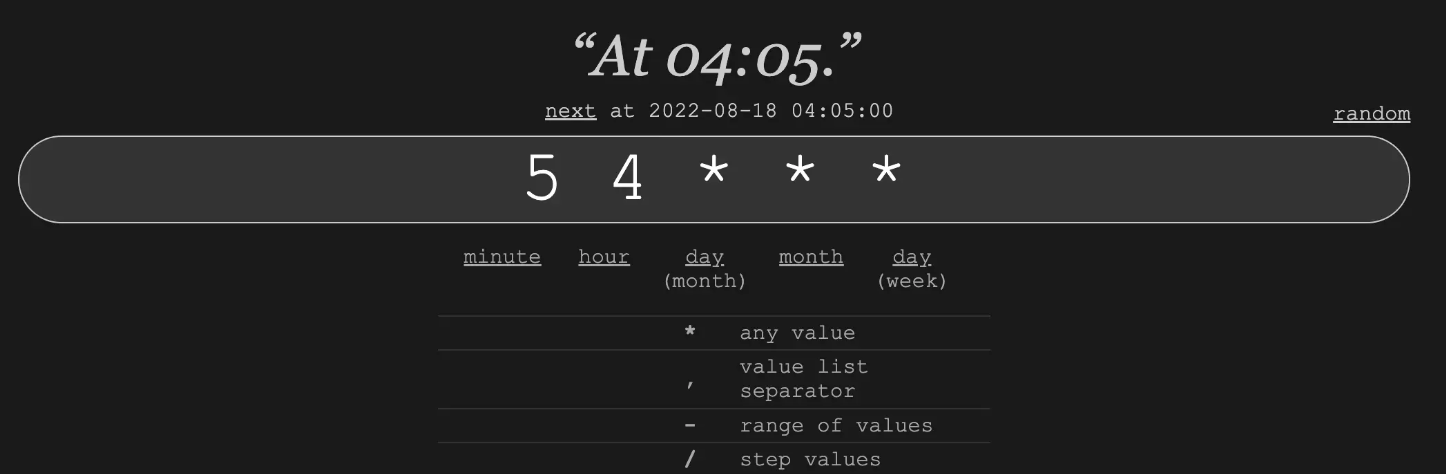

在 Unix-like 操作系统中,有一个大家都很熟悉的 cli 工具,它能够来处理定时任务,周期性任务,这就是: cron。 你只需要简单的语法控制就能实现任意【定时】的语义。用法上可以参考一下这个 Crontab Guru Editor,做的非常精巧。

简单说,每一个位都代表了一个时间维度,* 代表全集,所以,上面的语义是:在每天早上的4点05分触发任务。

但 cron 毕竟只是一个操作系统级别的工具,如果定时任务失败了,或者压根没启动,cron 是没法提醒开发者这一点的。并且,cron 和 正则表达式都有一种魔力,不知道大家是否感同身受,这里引用同事的一句名言:

这世界上有些语言非常相似: shell脚本, es查询的那个dsl语言, 定时任务的crontab, 正则表达式. 他们相似就相似在每次要写的时候基本都得重新现学一遍。

正巧,最近看到了 gron 这个开源项目,它是用 Golang 实现一个并发安全的定时任务库。实现非常简单精巧,代码量也不多。今天我们就来一起结合源码看一下,怎样基于 Golang 的能力做出来一个【定时任务库】。

gron

Gron provides a clear syntax for writing and deploying cron jobs.

gron 是一个泰国小哥在 2016 年开源的作品,它的特点就在于非常简单和清晰的语义来定义【定时任务】,你不用再去记 cron 的语法。我们来看下作为使用者怎样上手。

首先,我们还是一个 go get 安装依赖:

$ go get github.com/roylee0704/gron

假设我们期望在【时机】到了以后,要做的工作是打印一个字符串,每一个小时执行一次,我们就可以这样:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

"github.com/roylee0704/gron"

)

func main() {

c := gron.New()

c.AddFunc(gron.Every(1*time.Hour), func() {

fmt.Println("runs every hour.")

})

c.Start()

}非常简单,而且即便是在 c.Start 之后我们依然可以添加新的定时任务进去。支持了很好的扩展性。

定时参数

注意到我们调用 gron.New().AddFunc() 时传入了一个 gron.Every(1*time.Hour)。

这里其实你可以传入任何一个 time.Duration,从而把调度间隔从 1 小时调整到 1 分钟甚至 1 秒。

除此之外,gron 还很贴心地封装了一个 xtime 包用来把常见的 time.Duration 封装起来,这里我们开箱即用。

import "github.com/roylee0704/gron/xtime" gron.Every(1 * xtime.Day) gron.Every(1 * xtime.Week)

很多时候我们不仅仅某个任务在当天运行,还希望是我们指定的时刻,而不是依赖程序启动时间,机械地加 24 hour。gron 对此也做了很好的支持:

gron.Every(30 * xtime.Day).At("00:00")

gron.Every(1 * xtime.Week).At("23:59")我们只需指定 At("hh:mm") 就可以实现在指定时间执行。

源码解析

这一节我们来看看 gron 的实现原理。

所谓定时任务,其实包含两个层面:

- 触发器。即我们希望这个任务在什么时间点,什么周期被触发;

- 任务。即我们在触发之后,希望执行的任务,类比到我们上面示例的 fmt.Println。

对这两个概念的封装和扩展是一个定时任务库必须考虑的。

而同时,我们是在 Golang 的协程上跑程序的,意味着这会是一个长期运行的协程,否则你即便指定了【一个月后干XXX】这个任务,程序两天后挂了,也就无法实现你的诉求了。

所以,我们还希望有一个 manager 的角色,来管理我们的一组【定时任务】,如何调度,什么时候启动,怎么停止,启动了以后还想加新任务是否支持。

Cron

在 gron 的体系里,Cron 对象(我们上面通过 gron.New 创建出来的)就是我们的 manager,而底层的一个个【定时任务】则对应到 Cron 对象中的一个个 Entry:

// Cron provides a convenient interface for scheduling job such as to clean-up

// database entry every month.

//

// Cron keeps track of any number of entries, invoking the associated func as

// specified by the schedule. It may also be started, stopped and the entries

// may be inspected.

type Cron struct {

entries []*Entry

running bool

add chan *Entry

stop chan struct{}

}

// New instantiates new Cron instant c.

func New() *Cron {

return &Cron{

stop: make(chan struct{}),

add: make(chan *Entry),

}

}- entries 就是定时任务的核心能力,它记录了一组【定时任务】;

- running 用来标识这个 Cron 是否已经启动;

- add 是一个channel,用来支持在 Cron 启动后,新增的【定时任务】;

- stop 同样是个channel,注意到是空结构体,用来控制 Cron 的停止。这个其实是经典写法了,对日常开发也有借鉴意义,我们待会儿会好好看一下。

我们观察到,当调用 gron.New() 方法后,得到的是一个指向 Cron 对象的指针。此时只是初始化了 stop 和 add 两个 channel,没有启动调度。

Entry

重头戏来了,Cron 里面的 []*Entry 其实就代表了一组【定时任务】,每个【定时任务】可以简化理解为 <触发器,任务> 组成的一个 tuple。

// Entry consists of a schedule and the job to be executed on that schedule.

type Entry struct {

Schedule Schedule

Job Job

// the next time the job will run. This is zero time if Cron has not been

// started or invalid schedule.

Next time.Time

// the last time the job was run. This is zero time if the job has not been

// run.

Prev time.Time

}

// Schedule is the interface that wraps the basic Next method.

//

// Next deduces next occurring time based on t and underlying states.

type Schedule interface {

Next(t time.Time) time.Time

}

// Job is the interface that wraps the basic Run method.

//

// Run executes the underlying func.

type Job interface {

Run()

}- Schedule 代表了一个【触发器】,或者说一个定时策略。它只包含一个

Next方法,接受一个时间点,业务要返回下一次触发调动的时间点。 - Job 则是对【任务】的抽象,只需要实现一个

Run方法,没有入参出参。

除了这两个核心依赖外,Entry 结构还包含了【前一次执行时间点】和【下一次执行时间点】,这个目前可以忽略,只是为了辅助代码用。

按照时间排序

// byTime is a handy wrapper to chronologically sort entries.

type byTime []*Entry

func (b byTime) Len() int { return len(b) }

func (b byTime) Swap(i, j int) { b[i], b[j] = b[j], b[i] }

// Less reports `earliest` time i should sort before j.

// zero time is not `earliest` time.

func (b byTime) Less(i, j int) bool {

if b[i].Next.IsZero() {

return false

}

if b[j].Next.IsZero() {

return true

}

return b[i].Next.Before(b[j].Next)

}这里是对 Entry 列表的简单封装,因为我们可能同时有多个 Entry 需要调度,处理的顺序很重要。这里实现了 sort 的接口, 有了 Len(), Swap(), Less() 我们就可以用 sort.Sort() 来排序了。

此处的排序策略是按照时间大小。

新增定时任务

我们在示例里面出现过调用 AddFunc() 来加入一个 gron.Every(xxx) 这样一个【定时任务】。其实这是给用户提供的简单封装。

// JobFunc is an adapter to allow the use of ordinary functions as gron.Job

// If f is a function with the appropriate signature, JobFunc(f) is a handler

// that calls f.

//

// todo: possibly func with params? maybe not needed.

type JobFunc func()

// Run calls j()

func (j JobFunc) Run() {

j()

}

// AddFunc registers the Job function for the given Schedule.

func (c *Cron) AddFunc(s Schedule, j func()) {

c.Add(s, JobFunc(j))

}

// Add appends schedule, job to entries.

//

// if cron instant is not running, adding to entries is trivial.

// otherwise, to prevent data-race, adds through channel.

func (c *Cron) Add(s Schedule, j Job) {

entry := &Entry{

Schedule: s,

Job: j,

}

if !c.running {

c.entries = append(c.entries, entry)

return

}

c.add <- entry

}JobFunc 实现了我们上一节提到的 Job 接口,基于此,我们就可以让用户直接传入一个 func() 就ok,内部转成 JobFunc,再利用通用的 Add 方法将其加入到 Cron 中即可。

注意,这里的 Add 方法就是新增定时任务的核心能力了,我们需要触发器 Schedule,任务 Job。并以此来构造出一个定时任务 Entry。

若 Cron 实例还没启动,加入到 Cron 的 entries 列表里就ok,随后启动的时候会处理。但如果已经启动了,就直接往 add 这个 channel 中塞,走额外的新增调度路径。

启动和停止

// Start signals cron instant c to get up and running.

func (c *Cron) Start() {

c.running = true

go c.run()

}

// Stop halts cron instant c from running.

func (c *Cron) Stop() {

if !c.running {

return

}

c.running = false

c.stop <- struct{}{}

}我们先 high level 地看一下一个 Cron 的启动和停止。

- Start 方法执行的时候会先将 running 变量置为 true,用来标识实例已经启动(启动前后加入的定时任务 Entry 处理策略是不同的,所以这里需要标识),然后启动一个 goroutine 来实际跑启动的逻辑。

- Stop 方法则会将 running 置为 false,然后直接往 stop channel 塞一个空结构体即可。

ok,有了这个心里预期,我们来看看 c.run() 里面干了什么事:

var after = time.After

// run the scheduler...

//

// It needs to be private as it's responsible of synchronizing a critical

// shared state: `running`.

func (c *Cron) run() {

var effective time.Time

now := time.Now().Local()

// to figure next trig time for entries, referenced from now

for _, e := range c.entries {

e.Next = e.Schedule.Next(now)

}

for {

sort.Sort(byTime(c.entries))

if len(c.entries) > 0 {

effective = c.entries[0].Next

} else {

effective = now.AddDate(15, 0, 0) // to prevent phantom jobs.

}

select {

case now = <-after(effective.Sub(now)):

// entries with same time gets run.

for _, entry := range c.entries {

if entry.Next != effective {

break

}

entry.Prev = now

entry.Next = entry.Schedule.Next(now)

go entry.Job.Run()

}

case e := <-c.add:

e.Next = e.Schedule.Next(time.Now())

c.entries = append(c.entries, e)

case <-c.stop:

return // terminate go-routine.

}

}

}重点来了,看看我们是如何把上面 Cron, Entry, Schedule, Job 串起来的。

- 首先拿到 local 的时间 now;

- 遍历所有 Entry,调用 Next 方法拿到各个【定时任务】下一次运行的时间点;

- 对所有 Entry 按照时间排序(我们上面提过的 byTime);

- 拿到第一个要到期的时间点,在 select 里面通过 time.After 来监听。到点了就起动新的 goroutine 跑对应 entry 里的 Job,并回到 for 循环,继续重新 sort,再走同样的流程;

- 若 add channel 里有新的 Entry 被加进来,就加入到 Cron 的 entries 里,触发新的 sort;

- 若 stop channel 收到了信号,就直接 return,结束执行。

整体实现还是非常简洁的,大家可以感受一下。

Schedule

前面其实我们暂时将触发器的复杂性封装在 Schedule 接口中了,但怎么样实现一个 Schedule 呢?

尤其是注意,我们还支持 At 操作,也就是指定 Day,和具体的小时,分钟。回忆一下:

gron.Every(30 * xtime.Day).At("00:00")

gron.Every(1 * xtime.Week).At("23:59")这一节我们就来看看,gron.Every 干了什么事,又是如何支持 At 方法的。

// Every returns a Schedule reoccurs every period p, p must be at least

// time.Second.

func Every(p time.Duration) AtSchedule {

if p < time.Second {

p = xtime.Second

}

p = p - time.Duration(p.Nanoseconds())%time.Second // truncates up to seconds

return &periodicSchedule{

period: p,

}

}gron 的 Every 函数接受一个 time.Duration,返回了一个 AtSchedule 接口。我待会儿会看,这里注意,Every 里面是会把【秒】级以下给截掉。

我们先来看下,最后返回的这个 periodicSchedule 是什么:

type periodicSchedule struct {

period time.Duration

}

// Next adds time t to underlying period, truncates up to unit of seconds.

func (ps periodicSchedule) Next(t time.Time) time.Time {

return t.Truncate(time.Second).Add(ps.period)

}

// At returns a schedule which reoccurs every period p, at time t(hh:ss).

//

// Note: At panics when period p is less than xtime.Day, and error hh:ss format.

func (ps periodicSchedule) At(t string) Schedule {

if ps.period < xtime.Day {

panic("period must be at least in days")

}

// parse t naively

h, m, err := parse(t)

if err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

return &atSchedule{

period: ps.period,

hh: h,

mm: m,

}

}

// parse naively tokenises hours and minutes.

//

// returns error when input format was incorrect.

func parse(hhmm string) (hh int, mm int, err error) {

hh = int(hhmm[0]-'0')*10 + int(hhmm[1]-'0')

mm = int(hhmm[3]-'0')*10 + int(hhmm[4]-'0')

if hh < 0 || hh > 24 {

hh, mm = 0, 0

err = errors.New("invalid hh format")

}

if mm < 0 || mm > 59 {

hh, mm = 0, 0

err = errors.New("invalid mm format")

}

return

}可以看到,所谓 periodicSchedule 就是一个【周期性触发器】,只维护一个 time.Duration 作为【周期】。

periodicSchedule 实现 Next 的方式也很简单,把秒以下的截掉之后,直接 Add(period),把周期加到当前的 time.Time 上,返回新的时间点。这个大家都能想到。

重点在于,对 At 能力的支持。我们来关注下 func (ps periodicSchedule) At(t string) Schedule 这个方法

- 若周期连 1 天都不到,不支持 At 能力,因为 At 本质是在选定的一天内,指定小时,分钟,作为辅助。连一天都不到的周期,是要精准处理的;

- 将用户输入的形如 "23:59" 时间字符串解析出来【小时】和【分钟】;

- 构建出一个 atSchedule 对象,包含了【周期时长】,【小时】,【分钟】。

ok,这一步只是拿到了材料,那具体怎样处理呢?这个还是得继续往下走,看看 atSchedule 结构干了什么:

type atSchedule struct {

period time.Duration

hh int

mm int

}

// reset returns new Date based on time instant t, and reconfigure its hh:ss

// according to atSchedule's hh:ss.

func (as atSchedule) reset(t time.Time) time.Time {

return time.Date(t.Year(), t.Month(), t.Day(), as.hh, as.mm, 0, 0, time.UTC)

}

// Next returns **next** time.

// if t passed its supposed schedule: reset(t), returns reset(t) + period,

// else returns reset(t).

func (as atSchedule) Next(t time.Time) time.Time {

next := as.reset(t)

if t.After(next) {

return next.Add(as.period)

}

return next

}其实只看这个 Next 的实现即可。我们从 periodSchedule 那里获取了三个属性。

在调用 Next 方法时,先做 reset,根据原有 time.Time 的年,月,日,以及用户输入的 At 中的小时,分钟,来构建出来一个 time.Time 作为新的时间点。

此后判断是在哪个周期,如果当前周期已经过了,那就按照下个周期的时间点返回。

到这里,一切就都清楚了,如果我们不用 At 能力,直接 gron.Every(xxx),那么直接就会调用

t.Truncate(time.Second).Add(ps.period)

拿到一个新的时间点返回。

而如果我们要用 At 能力,指定当天的小时,分钟。那就会走到 periodicSchedule.At 这里,解析出【小时】和【分钟】,最后走 Next 返回 reset 之后的时间点。

这个和 gron.Every 方法返回的 AtSchedule 接口其实是完全对应的:

// AtSchedule extends Schedule by enabling periodic-interval & time-specific setup

type AtSchedule interface {

At(t string) Schedule

Schedule

}直接就有一个 Schedule 可以用,但如果你想针对天级以上的 duration 指定时间,也可以走 At 方法,也会返回一个 Schedule 供我们使用。

扩展性

gron 里面对于所有的依赖也都做成了【依赖接口而不是实现】。Cron 的 Add 函数的入参也是两个接口,这里可以随意替换:func (c *Cron) Add(s Schedule, j Job)。

最核心的两个实体依赖 Schedule, Job 都可以用你自定义的实现来替换掉。

如实现一个新的 Job:

type Reminder struct {

Msg string

}

func (r Reminder) Run() {

fmt.Println(r.Msg)

}事实上,我们上面提到的 periodicSchedule 以及 atSchedule 就是 Schedule 接口的具体实现。我们也完全可以不用 gron.Every,而是自己写一套新的 Schedule 实现。只要实现 Next(p time.Duration) time.Time 即可。

我们来看一个完整用法案例:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/roylee0704/gron"

"github.com/roylee0704/gron/xtime"

)

type PrintJob struct{ Msg string }

func (p PrintJob) Run() {

fmt.Println(p.Msg)

}

func main() {

var (

// schedules

daily = gron.Every(1 * xtime.Day)

weekly = gron.Every(1 * xtime.Week)

monthly = gron.Every(30 * xtime.Day)

yearly = gron.Every(365 * xtime.Day)

// contrived jobs

purgeTask = func() { fmt.Println("purge aged records") }

printFoo = printJob{"Foo"}

printBar = printJob{"Bar"}

)

c := gron.New()

c.Add(daily.At("12:30"), printFoo)

c.AddFunc(weekly, func() { fmt.Println("Every week") })

c.Start()

// Jobs may also be added to a running Gron

c.Add(monthly, printBar)

c.AddFunc(yearly, purgeTask)

// Stop Gron (running jobs are not halted).

c.Stop()

}经典写法-控制退出

这里我们还是要聊一下 Cron 里控制退出的经典写法。我们把其他不相关的部分清理掉,只留下核心代码:

type Cron struct {

stop chan struct{}

}

func (c *Cron) Stop() {

c.stop <- struct{}{}

}

func (c *Cron) run() {

for {

select {

case <-c.stop:

return // terminate go-routine.

}

}

}空结构体能够最大限度节省内存,毕竟我们只是需要一个信号。核心逻辑用 for + select 的配合,这样当我们需要结束时可以立刻响应。非常经典,建议大家日常有需要的时候采用。

结语

gron 整体代码其实只在 cron.go 和 schedule.go 两个文件,合起来代码不过 300 行,非常精巧,基本没有冗余,扩展性很好,是非常好的入门材料。

不过,作为一个 cron 的替代品,其实 gron 还是有自己的问题的。简单讲就是,如果我重启了一个EC2实例,那么我的 cron job 其实也还会继续执行,这是落盘的,操作系统级别的支持。

但如果我执行 gron 的进程挂掉了,不好意思,那就完全凉了。你只有重启,然后再把所有任务加回来才行。而我们既然要用 gron,是很有可能定一个几天后,几个星期后,几个月后这样的触发器的。谁能保证进程一直活着呢?连机子本身都可能重启。

所以,我们需要一定的机制来保证 gron 任务的可恢复性,将任务落盘,持久化状态信息,算是个思考题,这里大家可以考虑一下怎么做。

加载全部内容