Go并发编程goroutine Go并发编程之goroutine使用正确方法

深度思维者 人气:0并发(concurrency): 指在同一时刻只能有一条指令执行,但多个进程指令被快速的轮换执行,使得在宏观上具有多个进程同时执行的效果,但在微观上并不是同时执行的,只是把时间分成若干段,通过cpu时间片轮转使多个进程快速交替的执行。

1. 对创建的gorouting负载

1.1 不要创建一个你不知道何时退出的 goroutine

下面的代码有什么问题? 是不是在我们的程序种经常写类似的代码?

// Week03/blog/01/01.go

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

_ "net/http/pprof"

)

// 初始化函数

func setup() {

// 这里面有一些初始化的操作

}

// 入口函数

func main() {

setup()

// 主服务

server()

// for debug

pprof()

select {}

}

// http api server

func server() {

go func() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

})

// 主服务

if err := http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux); err != nil {

log.Panicf("http server err: %+v", err)

return

}

}()

}

// 辅助服务,用来debug性能测试

func pprof() {

// 辅助服务,监听了其他端口,这里是 pprof 服务,用于 debug

go http.ListenAndServe(":8081", nil)

}

以上代码有几个问题,是否想到过?

- 如果

server是在其他的包里面, 如果没有特殊的说明, 调用者是否知道这是一个异步调用? main函数种,最后使用select {}使整个程序处于阻塞状态,也就是空转, 会不会存在浪费?- 如果线上出现事故,debug服务已经突出,你想要debug这时是否很茫然?

- 如果某一天服务突然重启, 你却找不到事故日志, 是否能想到起的这个

8801端口的服务呢?

1.2 不要帮别人做选择

把是否 并发 的选择权交给你的调用者,而不是自己就直接悄悄的用上了 goroutine

下面做如下改变,将两个函数是否并发操作的选择权留给main函数

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

_ "net/http/pprof"

)

func setup(){

// 初始化操作

}

func main(){

setup()

// for debug

go pprof()

// 主服务,http api

go server()

select{}

}

func server(){

mux := http.NewServerMux()

mux.HandleFunc("ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r * http.Request){

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

}

// 主服务

if err := http.ListerAndServer(":8080",mux); err != nil{

log.panic("http server launch error: %v", err)

return

}

}

func pprof(){

// 辅助服务 监听其他端口,这里是pprof服务,拥有debug

http.ListerAndServer(":8081",nil)

}

1.3 不要作为一个旁观者

一般情况下,不要让 主进程称为一个无所事事的旁观者, 明明可以干活,但是最后使用一个select在那儿空跑,而且这种看着也怪,在没有特殊场景下尽量不要使用这种阻塞的方式

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

_ "net/http/pprof"

)

func setup() {

// 这里面有一些初始化的操作

}

func main() {

setup()

// for debug

go pprof()

// 主服务, http本来就是一个阻塞的服务

server()

}

func server() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

})

// 主服务

if err := http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux); err != nil {

log.Panicf("http server err: %+v", err)

return

}

}

func pprof() {

// 辅助服务,监听了其他端口,这里是 pprof 服务,用于 debug

http.ListenAndServe(":8081", nil)

}

1.4 不要创建不知道什么时候退出的 goroutine

很多时候我们在创建一个 协程(goroutine)后就放任不管了,如果程序永远运行下去,可能不会有什么问题,但实际情况并非如此, 我们的产品需要迭代,需要修复bug,需要不停进行构建,发布, 所以当程序退出后(主程序),运行的某些子程序并不会完全退出,比如这个 pprof, 他自身本来就是一个后台服务,但是当 main退出后,实际 pprof这个服务并不会退出,这样 pprof就会称为一个孤魂野鬼,称为一个 zombie, 导致goroutine泄漏。

所以再一次对程序进行修改, 保证 goroutine能正常退出

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

_ "net/http/pprof"

"time"

)

func setup() {

// 这里面有一些初始化的操作

}

func main() {

setup()

// 用于监听服务退出, 这里使用了两个 goroutine,所以 cap 为2

done := make(chan error, 2)

// 无缓冲的通道,用于控制服务退出,传入同一个 stop,做到只要有一个服务退出了那么另外一个服务也会随之退出

stop := make(chan struct{}, 0)

// for debug

go func() {

// pprof 传递一个 channel

fmt.Println("pprof start...")

done <- pprof(stop)

fmt.Printf("err1:%v\n", done)

}()

// 主服务

go func() {

fmt.Println("app start...")

done <- app(stop)

fmt.Printf("err2:%v\n", done)

}()

// stopped 用于判断当前 stop 的状态

var stopped bool

// 这里循环读取 done 这个 channel

// 只要有一个退出了,我们就关闭 stop channel

for i := 0; i < cap(done); i++ {

// 对于有缓冲的chan, chan中无值会一直处于阻塞状态

// 对于app 服务会一直阻塞状态,不会有 数据写入到done 通道,只有在5s后,模拟的 pprof会有err写入chan,此时才会触发以下逻辑

if err := <-done; err != nil {

log.Printf("server exit err: %+v", err)

}

if !stopped {

stopped = true

// 通过关闭 无缓冲的channel 来通知所有的 读 stop相关的goroutine退出

close(stop)

}

}

}

// http 服务

func app(stop <-chan struct{}) error {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

})

return server(mux, ":8080", stop)

}

func pprof(stop <-chan struct{}) error {

// 注意这里主要是为了模拟服务意外退出,用于验证一个服务退出,其他服务同时退出的场景

// 因为这里没有返回err, 所以done chan中无法接收到值, 主程序中会一直阻塞住

go func() {

server(http.DefaultServeMux, ":8081", stop)

}()

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

// 模拟出错

return fmt.Errorf("mock pprof exit")

}

// 启动一个服务

func server(handler http.Handler, addr string, stop <-chan struct{}) error {

s := http.Server{

Handler: handler,

Addr: addr,

}

// 这个 goroutine 控制退出,因为 stop channel 只要close或者是写入数据,这里就会退出

go func() {

// 无缓冲channel等待,写入或者关闭

<-stop

log.Printf("server will exiting, addr: %s", addr)

// 此时 httpApi 服务就会优雅的退出

s.Shutdown(context.Background())

}()

// 没有触发异常的话,会一直处于阻塞

return s.ListenAndServe()

}

查看以下运行结果

D:\gopath\controlGoExit>go run demo.go

app start...

pprof start...

err1:0xc00004c720

2021/09/12 22:48:37 server exit err: mock pprof exit

2021/09/12 22:48:37 server will exiting, addr: :8080

2021/09/12 22:48:37 server will exiting, addr: :8081

err2:0xc00004c720

2021/09/12 22:48:37 server exit err: http: Server closed

虽然我们已经经过了三轮优化,但是这里还是有一些需要注意的地方:

- 虽然我们调用了 Shutdown 方法,但是我们其实并没有实现优雅退出

- 在 server 方法中我们并没有处理 panic的逻辑,这里需要处理么?如果需要那该如何处理呢?

1.5 不要创建都无法退出的 goroutine

永远无法退出的 goroutine, 即 goroutine 泄漏

下面是一个例子,可能在不知不觉中会用到

package main

import (

"log"

_ "net/http/pprof"

"net/http"

)

func setup() {

// 这里面有一些初始化的操作

log.Print("服务启动初始化...")

}

func main() {

setup()

// for debug

go pprof()

// 主服务, http本来就是一个阻塞的服务

server()

}

func server() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

})

mux.HandleFunc("/leak", LeakHandle)

// 主服务

if err := http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux); err != nil {

log.Panicf("http server err: %+v", err)

return

}

}

func pprof() {

// 辅助服务,监听了其他端口,这里是 pprof 服务,用于 debug

http.ListenAndServe(":8081", nil)

}

func LeakHandle(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ch := make(chan bool, 0)

go func() {

fmt.Println("异步任务做一些操作")

<-ch

}()

w.Write([]byte("will leak"))

}

复用一下上面的 server 代码,我们经常会写出这种类似的代码

- http 请求来了,我们启动一个 goroutine 去做一些耗时一点的工作

- 然后返回了

- 然后之前创建的那个 goroutine 阻塞了(对于一个无缓冲的chan,如果没有接收或关闭操作会永远阻塞下去)

- 然后就泄漏了

绝大部分的 goroutine 泄漏都是因为 goroutine 当中因为各种原因阻塞了,我们在外面也没有控制它退出的方式,所以就泄漏了

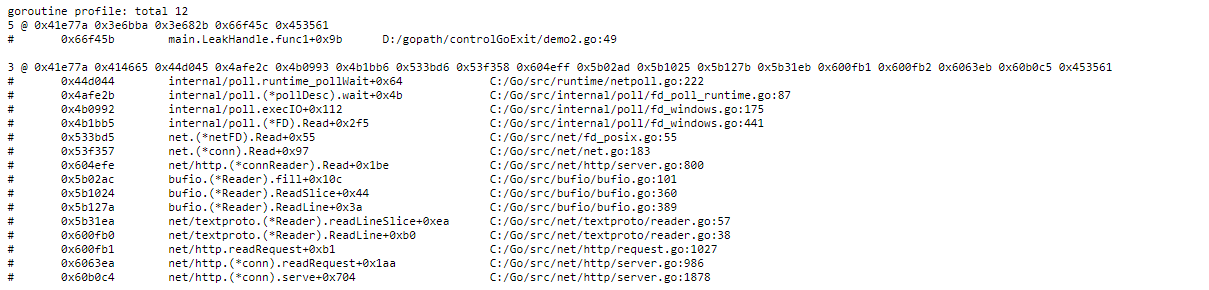

接下来我们验证一下是不是真的泄漏了

服务启动之后,访问debug访问网址,http://localhost:8081/debug/pprof/goroutine?debug=1.

当请求两次 http://127.0.0.1/leak后查看 goroutine数量,如图

继续请求三次后,如图

1.6 确保创建出的goroutine工作已经完成

这个其实就是优雅退出的问题,程序中可能启动了很多的 goroutine 去处理一些问题,但是服务退出的时候我们并没有考虑到就直接退出了。例如退出前日志没有 flush 到磁盘,我们的请求还没完全关闭,异步 worker 中还有 job 在执行等等。

看一个例子,假设现在有一个埋点服务,每次请求我们都会上报一些信息到埋点服务上

// Reporter 埋点服务上报

type Reporter struct {

}

var reporter Reporter

// 模拟耗时

func (r Reporter) report(data string) {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

fmt.Printf("report: %s\n", data)

}

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// 在请求中异步调用

// 这里并没有满足一致性

go reporter.report("ping pong")

fmt.Println("ping")

w.Write([]byte("pong"))

})

在发送一次请后之后就直接退出了, 异步上报的逻辑是没有执行的

$ go tun demo.go ping ^C signal:interrupt

有两种改法:

- 一种是给 reporter 加上 shutdown 方法,类似 http 的 shutdown,等待所有的异步上报完成之后,再退出

- 另外一种是我们直接使用 一些 worker 来执行,在当然这个 worker 也要实现类似 shutdown 的方法。

一般推荐后一种,因为这样可以避免请求量比较大时,创建大量 goroutine,当然如果请求量比较小,不会很大,用第一种也是可以的。

第二种方法代码如下:

// 埋点上报

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"sync"

)

// Reporter 埋点服务上报

type Reporter struct {

worker int

messages chan string

wg sync.WaitGroup

closed chan struct{}

once sync.Once

}

// NewReporter NewReporter

func NewReporter(worker, buffer int) *Reporter {

return &Reporter{

worker: worker,

messages: make(chan string, buffer),

closed: make(chan struct{}),

}

}

// 执行上报

func (r *Reporter) Run(stop <-chan struct{}) {

// 用于执行错误

go func() {

// 没有错误时

<-stop

fmt.Println("stop...")

r.shutdown()

}()

for i := 0; i < r.worker; i++ {

r.wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer r.wg.Done()

for {

select {

case <-r.closed:

return

case msg := <-r.messages:

fmt.Printf("report: %s\n", msg)

}

}

}()

}

r.wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("report workers exit...")

}

// 这里不必关闭 messages

// 因为 closed 关闭之后,发送端会直接丢弃数据不再发送

// Run 方法中的消费者也会退出

// Run 方法会随之退出

func (r *Reporter) shutdown() {

r.once.Do(func() { close(r.closed) })

}

// 模拟耗时

func (r *Reporter) Report(data string) {

// 这个是为了及早退出

// 并且为了避免我们消费者能力很强,发送者这边一直不阻塞,可能还会一直写数据

select {

case <-r.closed:

fmt.Printf("reporter is closed, data will be discarded: %s \n", data)

default:

}

select {

case <-r.closed:

fmt.Printf("reporter is closed, data will be discarded: %s \n", data)

case r.messages <- data:

}

}

func setup3() {

// 初始化一些操作

fmt.Println("程序启动...")

}

func main() {

setup3()

// 用于监听服务完成时退出

done := make(chan error, 3)

// 实例化一个 reporter

reporter := NewReporter(2, 100)

// 用于控制服务退出,传入同一个 stop,做到只要有一个服务退出了那么另外一个服务也会随之退出

stop := make(chan struct{}, 0)

// for debug

go func() {

done <- pprof3(stop)

}()

// http主服务

go func() {

done <- app3(reporter, stop)

}()

// 上报服务,接收一个监控停止的 chan

go func() {

reporter.Run(stop)

done <- nil

}()

// 这里循环读取 done 这个 channel

// 只要有一个退出了,我们就关闭 stop channel

for i := 0; i < cap(done); i++ {

// 对于有缓冲的chan, chan中无值会一直处于阻塞状态

// 对于app 服务会一直阻塞状态,不会有 数据写入到done 通道,只有在5s后,模拟的 pprof会有err写入chan,此时才会触发以下逻辑

if err := <-done; err != nil {

log.Printf("server exit err: %+v", err)

}

// 通过关闭 无缓冲的channel 来通知所有的 读 stop相关的goroutine退出

close(stop)

}

}

func pprof3(stop <-chan struct{}) error {

// 辅助服务,监听了其他端口,这里是 pprof 服务,用于 debug

err := server3(http.DefaultServeMux, ":8081", stop)

return err

}

func app3(report *Reporter, stop <-chan struct{}) error {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/ping", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// 在请求中异步调用

// 这里并没有满足一致性

go report.Report("ping pong")

fmt.Println("ping")

_, err := w.Write([]byte("pong"))

if err != nil {

log.Println("response err")

}

})

return server3(mux, ":8080", stop)

}

// 启动一个服务

func server3(handler http.Handler, addr string, stop <-chan struct{}) error {

s := http.Server{

Handler: handler,

Addr: addr,

}

// 这个 goroutine 控制退出,因为 stop channel 只要close 或者是写入数据,这里就会退出

go func() {

// 无缓冲channel等待,写入或者关闭

<-stop

log.Printf("server will exiting, addr: %s", addr)

// 此时 httpApi 服务就会优雅的退出

err := s.Shutdown(context.Background())

if err != nil {

log.Printf("server exiting occur error, %s", err.Error())

}

}()

// 没有触发异常的化,会一直处于阻塞

return s.ListenAndServe()

}

上面代码应该还有问题,等日后再做优化

第一种方法参考:reporter 添加shutdown方法

2. 总结

在使用go语言初期, 使用一个go关键字轻松开启一个异步协程,再加上chan很容易实现 生产者---》消费者 设计模型,但是在使用过程中往往忽略了 程序退出时资源回收的问题,也很容易写成一个数据使用一个go来处理,虽然官方说明了 创建一个goroutine的占用资源很小,但是再小的 占用空间也敌不过一个死循环啊。 所以在使用gorouine创建协程除了注意正确规定线程数以为,也要注意以下几点。

- 将是否异步调用的选择泉交给调用者, 不然很有可能使用者不知道所调用的函数立使用了

go - 如果要启动一个

goroutine, 要对他负责

不用启动一个无法控制他退出或者无法知道何时退出的goroutine

启动goroutine时加上 panic recovery机制,避免服务直接不可用,可以使用如下代码

// DeferRecover defer recover from panic.

func DeferRecover(tag string, handlePanic func(error)) func() {

return func() {

if err := recover(); err != nil {

log.Errorf("%s, recover from: %v\n%s\n", tag, err, debug.Stack())

if handlePanic != nil {

handlePanic(fmt.Errorf("%v", err))

}

}

}

}

// WithRecover recover from panic.

func WithRecover(tag string, f func(), handlePanic func(error)) {

defer DeferRecover(tag, handlePanic)()

f()

}

// Go is a wrapper of goroutine with recover.

func Go(name string, f func(), handlePanic func(error)) {

go WithRecover(fmt.Sprintf("goroutine %s", name), f, handlePanic)

}

- 造成 goroutine 泄漏的主要原因就是 goroutine 中造成了阻塞,并且没有外部手段控制它退出

尽量避免在请求中直接启动 goroutine 来处理问题,而应该通过启动 worker 来进行消费,这样可以避免由于请求量过大,而导致大量创建 goroutine 从而导致 oom,当然如果请求量本身非常小,那当我没说

3. 参考

https://dave.cheney.net/practical-go/presentations/qcon-china.html

https://lailin.xyz/post/go-training-week3-goroutine.html#总结

https://www.ardanlabs.com/blog/2019/04/concurrency-trap-2-incomplete-work.html

https://www.ardanlabs.com/blog/2014/01/concurrency-goroutines-and-gomaxprocs.html

加载全部内容